What do you picture when you hear the words “road rage”? Maybe it’s the family member or friend who spends their entire commute effing and blinding about other drivers from their steering wheel. Maybe it’s someone getting out of their car to shout at the driver behind them. Maybe a fist-fight in the middle of the road?

“Road rage” isn’t a well-defined concept, encompassing everything from someone being a bit annoyed in their own car, to making angry gestures out the window, to full-on violence at the side of the road. We don’t keep crime statistics on road rage in Ireland, because road rage in itself – being angry – isn’t the crime. It can lead to crimes, but they are generally recorded under whatever type of offence they are: dangerous driving, harassment, assault, etc. However, when we asked drivers in our latest AA survey if they had ever been on the receiving end of someone’s road rage, we discovered that it is very prevalent on our roads – 70% said yes.

Perhaps surprisingly, in most cases, the road rage people described was not the stereotypical “fisticuffs on the road” version. Only 1% of our 8,200 respondents said their experience included physical violence. 1 in 4 drivers have experienced a verbal altercation with another driver, but the most common type of road rage people recognised was aggressive driving. Over half of drivers say they have experienced things like dangerous overtaking, beeping or flashing lights in a bid to make them go faster or pull over, tailgating aggressively, and so-called “brake-testing”: pulling in in front of them and hitting the brakes, almost resulting in a collision.

Over 1 in 3 (35%) think road rage has gotten worse in the last 2 years, perhaps with the stresses of the pandemic looming. But more say it’s equally bad now as it was 2 years ago (2 in 5 or 40%), and very few (7%) think it has improved.

What about their own behaviour?

An overwhelming majority (98%) have felt annoyed at another driver’s behaviour – and 3 in 4 said this is a reasonably regular occurrence for them (happening “sometimes” or “often”). 2 in 5 said they find driving to be a stressful experience at least “sometimes”, and a third confessed that they feel more impatient with other drivers when the traffic is bad.

However, in general, people don’t let this annoyance or stress build into an actual confrontation. The vast majority (96%) have never left their car to confront another road user. Over 6 in 10 admit to shouting insults about others inside their car, but this drops to just 3 in 10 if they think the other person is actually able to hear them. Almost three quarters said they have beeped at other drivers to let them know they were in the wrong, but most of them say it’s “rare” for them to do so – only 3% say they do this often.

Types of road rage – drivers’ experiences

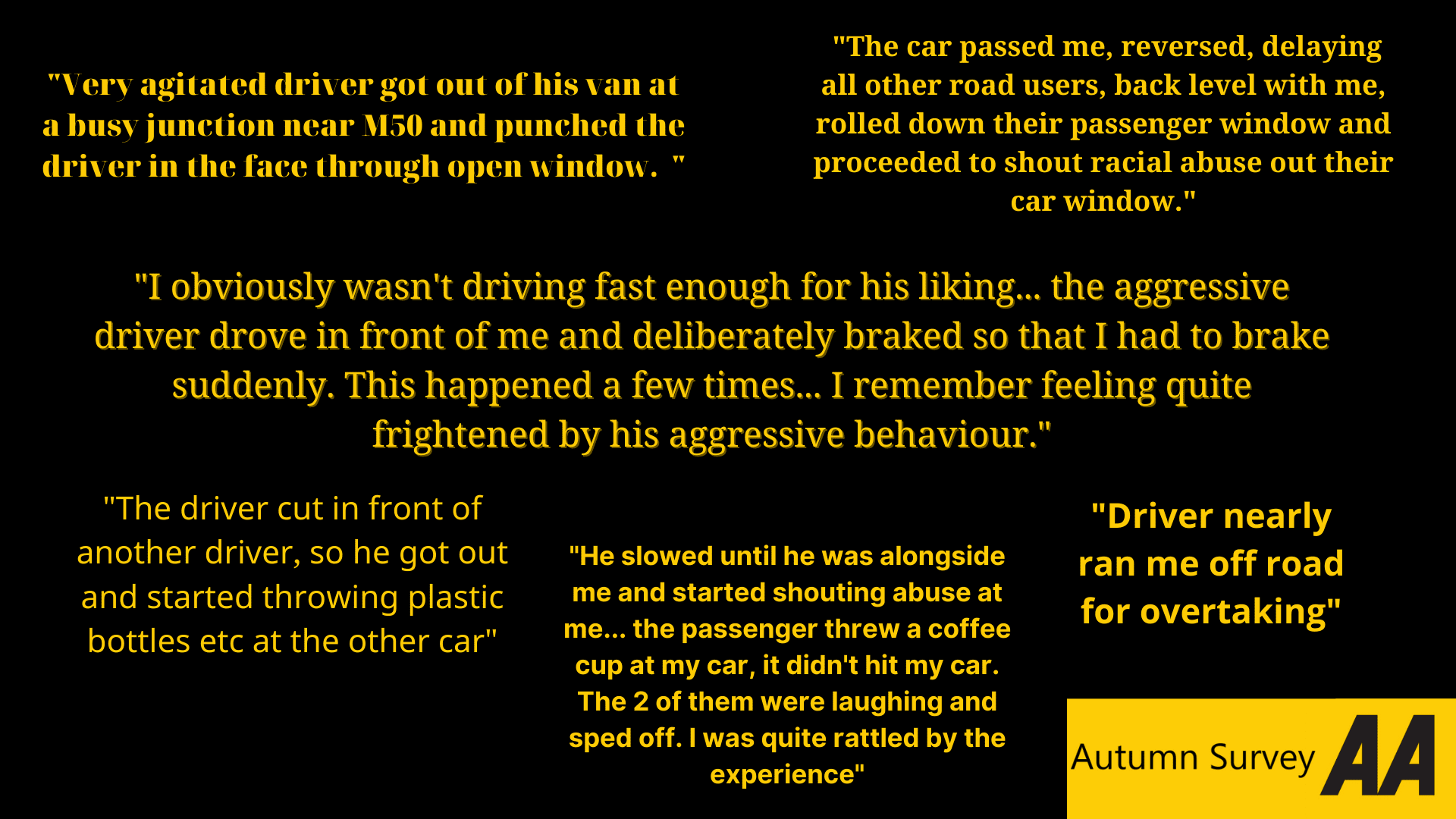

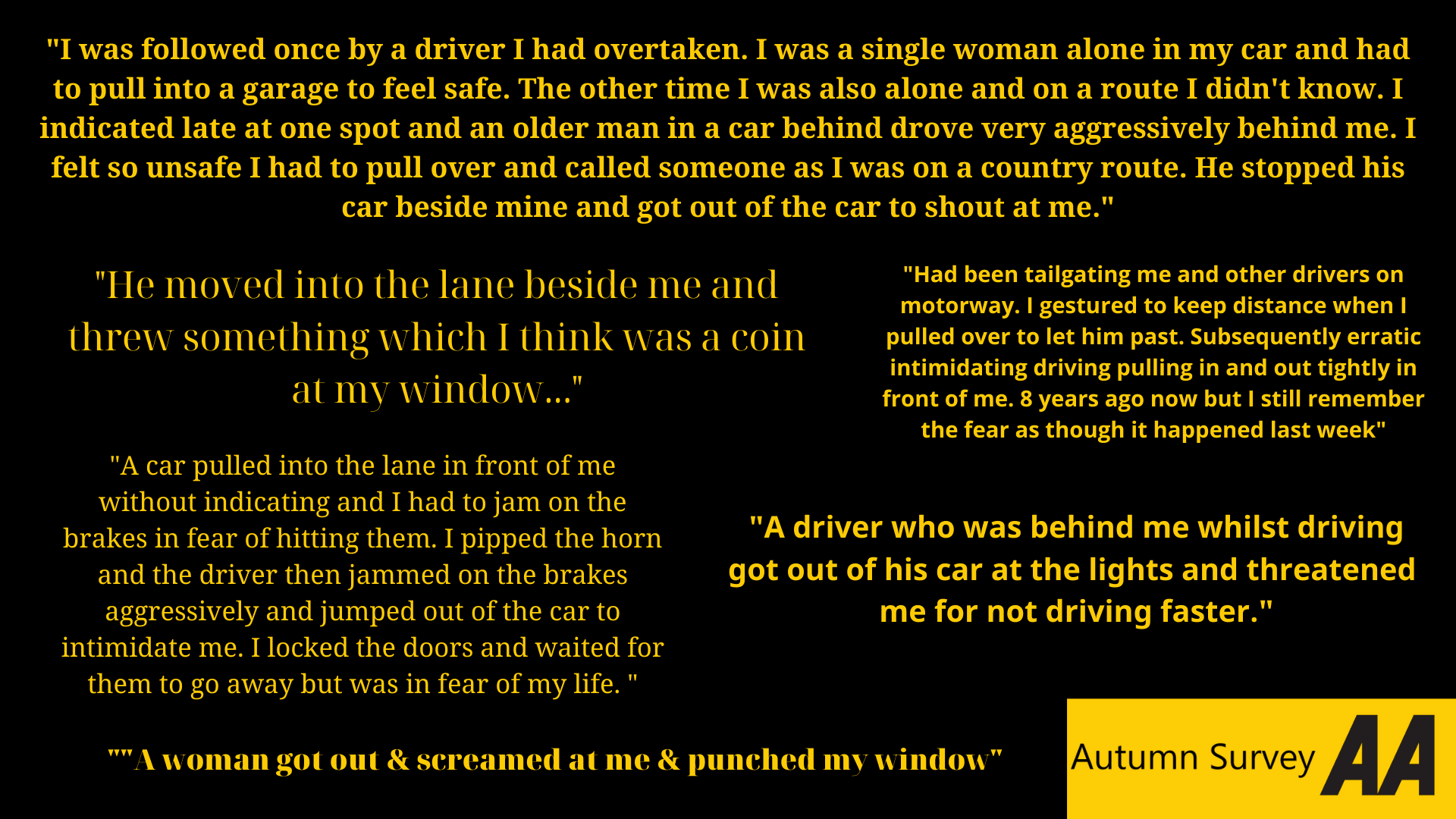

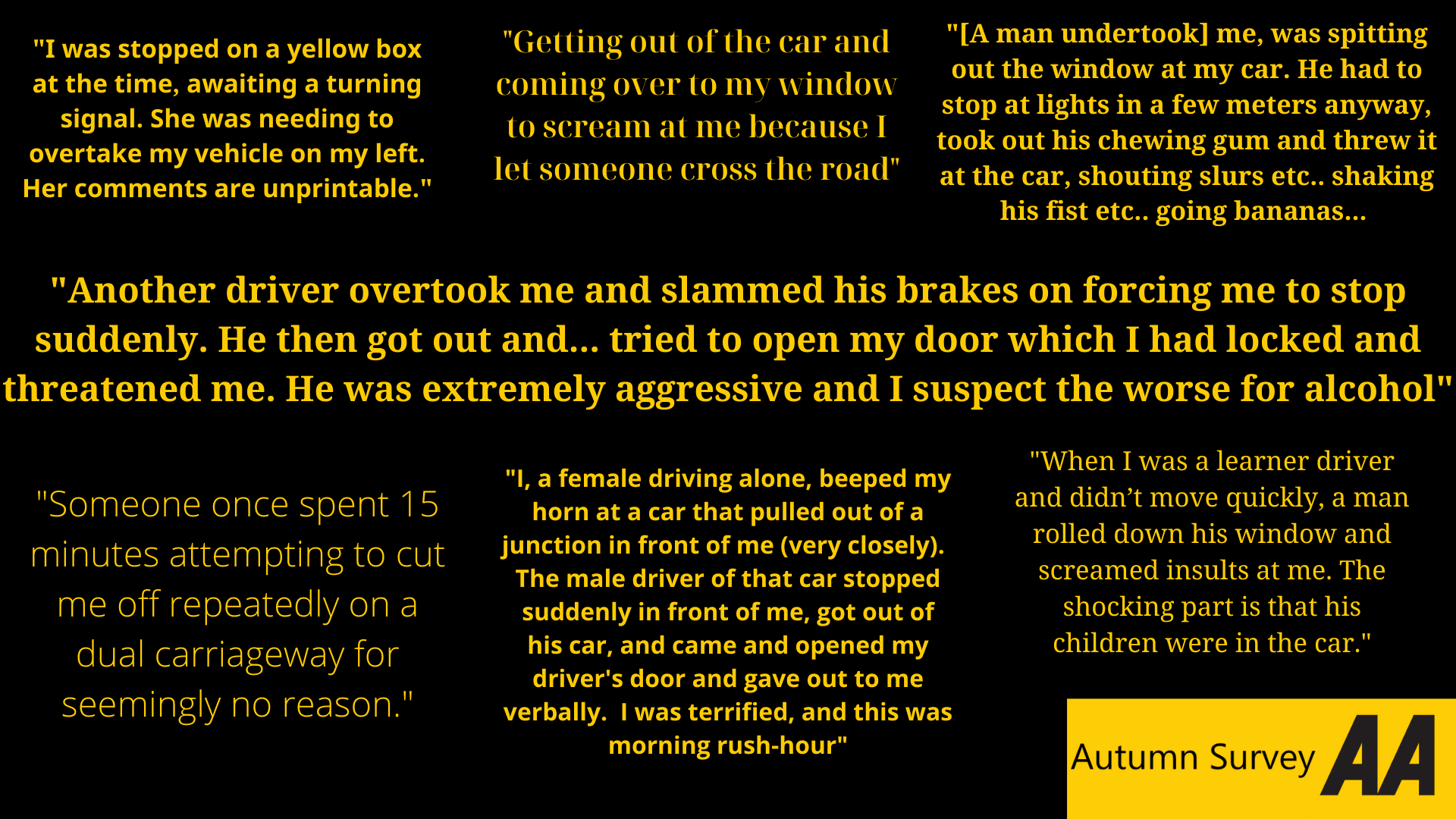

Over 800 survey respondents told us about specific experiences they had with raging drivers. More than 300 of their stories involved cases of an impatient driver trying to persuade them to move faster or get out of the way, even if they were at the speed limit.

Aggressive tailgating, beeping, flashing of lights and shouting while overtaking were common factors, as well as so-called brake-testing: when a driver pulls in sharply in front and then hits the brakes, often as a form of “revenge” for overtaking them.

People told us about having items thrown at their cars or through their windows: plastic bottles, lit cigarettes, coins, coffee cups, beer cans and chewing gum. Several respondents, mainly women, told us of being followed by angry drivers for several kilometres, or even all the way to their destination. Some people had experienced confrontations, where another driver stopped the car and got out to berate or threaten them. A smaller proportion of the stories involved physical violence outside the vehicle: a punch thrown, an attempt to pull someone out of a vehicle, and a baseball bat, a shovel and a hurley swung at cars.

Whether it involved violence, aggressive driving or a threat, lots of respondents told us that their experience had left them shaken or nervous driving in the same scenarios again.

What causes road rage?

Like any emotion, it can be difficult sometimes to pin-point the actual root of road rage. It’s often triggered by a perceived transgression by another driver – things like pulling out, overtaking, not moving off quickly enough. These things may be irritating, but in people with road rage, they lead to an over-reaction of anger.

When we asked Paul Hunter from the Cork Hypnosis Clinic, who provides therapy for people who struggle with road rage, he said “In some people, it’s pure anger, based on their background. In other people, it can be a fear response: the fear that another person is taking advantage of them, or a fear that another person is getting the upper hand or, or [the fear of] losing control.”

Driving has some inherent features that make frustration or anger likely: unexpected traffic jams can be stressful when you don’t know what’s happening, or when you’re now running late and feel that you don’t have any control over it. Furthermore, when people are in cars, they are effectively in bubbles – communication is harder, and it’s not always possible to figure out another driver’s intentions.

Jack Katz, an American sociologist who wrote about road rage in LA in his 1999 book “How Emotions Work”, found that pre-existing anger or fear didn’t explain all cases of road rage. He argues that the lack of communication or “asymmetrical awareness” between drivers is a key reason in many cases. He says driving can be “a kind of endless Rorschach test” of figuring out what other drivers mean. On top of this, he outlines that drivers tend to see their car as an extension of themselves, which is a necessary side-effect of driving: to move the car through the world, you have to embody it, knowing where it is in relation to others. And because of the lack of communication, any perceived transgressions by another driver can feel like a personal insult to them. They feel like the other driver didn’t see or respect them as a person. He says things like brake testing are “a common way of registering a complaint: you didn’t pay attention to me before, but now you certainly will!”.

As such, aggressive driving can be seen as an attempt to express an emotion that would normally be done through facial expressions and body language. Mayo County Council’s Road Safety Office has run numerous safety campaigns around road rage, and their Road Safety Officer Christina Lynch refers to tailgating and aggressive driving as “autobody language”. She says “That triggers the other driver to do it back, and that escalation of tension leads to collisions”.

Jack Katz found that often a passenger in the same car, who witnessed the same event, didn’t feel slighted or enraged in the same way as the driver did. The passenger might feel fear, or even amusement, but they don’t take it as personally as the driver. The driver feels personally victimised, like they have been treated as a non-person – and then, they may even feel angry that they have been made feel angry.

Paul Hunter also points to a dehumanising element, but on the other side of the equation. Once a driver has been consumed by the anger, they can no longer see the situation clearly. “In a full-blown road rage incident, what’s essentially happening is you’re getting tunnel vision. You’re getting the blocking out of the idea that there’s a human being in that other car and it’s just an object; it’s something where you can leave off steam.”

Jack Katz’s research showed that small gestures between drivers – acknowledging others by a wave of the hand or a quick flash of the lights – could help overcome the communication barrier and diffuse the anger in some situations. That’s something that holds up in our survey: over 9 in 10 drivers say they like when someone acknowledges them after a mistake, or after a favour, like letting them out.

Of course, road rage isn’t always about the road at all. Paul Hunter says when he treats someone for road rage, he will look for a root cause: “With hypnosis, it is first of all and fundamentally learning how to relax, because in all my time dealing with people who’ve had road rage, they’re not very relaxed people in general. The second thing is clearing out whichever other issues are causing this […]. The funny thing is that when I deal with people with road rage, about 75% of the time we’re not talking about road rage, we’re talking about other issues.”

Sometimes, a person can be angry about something else entirely that happened before they got into the car, or a situation that’s been bubbling away in their personal life. If someone is annoyed already because they have had a row with their partner, or there was trouble at work, or someone was rude to them in the shop, then a small thing on the roads can spark the match and cause their temper to flare. People talk about the “red mist” descending – they were already annoyed, and the driver that pulled out in front of them, or slowed down so that they missed the lights, tipped them into unreasonable anger.

So what do you do if it happens to you?

If you find yourself on the tail end of someone’s road rage, the best advice is to lock your car doors, and not to react. This can be difficult. But as hypnotherapist Paul Hunter says the rager is in tunnel-vision mode and flooded by their anger. “You can’t converse with a person that’s in road rage, because they’re not in a mood to make sense, they’re flooded. You can’t get through to them, so it’s really kind of pointless engaging with them”

His advice? Don’t copy them. “It’s about remaining calm yourself. I’d always suggest to people: don’t get out of the car.”

This is reiterated by Road Safety Office Christina Lynch: “If someone is provoking you, don’t look back, don’t gesture, don’t press that horn for a very long time, and share the road with cyclists and pedestrians. You don’t want to invite [the road rager] to a bigger problem, and if you’re driving away, you’re never going to see that person again.”

Of course, if someone is being extremely violent or aggressive towards your vehicle while stopped, you should call the Gardaí straight away. And if someone is driving aggressively around you, or you think they are following you, change your route. Drive to a busy and well-lit area, or pull in to the nearest Garda station.

What if you’re the person with road rage?

Driving with road rage is dangerous – at the end of the day, a vehicle is a piece of heavy machinery that needs care and attention in order not to cause serious damage. You should never drive in an angry or distressed emotional state.

If you know you are prone to getting a little angry or irritable on the roads, Paul Hunter suggests making the journey enjoyable – put on your favourite album or an audiobook. It’s about changing your attitude towards the journey ahead and reframing it in your head: “What people should do when they get into a car is think ‘This is going to be great fun – this is going to be enjoyable’.” You should also leave yourself more time for a journey so that an unexpected hold-up won’t tip you into unbridled frustration.

Christina Lynch from Mayo CoCo also suggests playing music at a moderate volume to make the drive enjoyable, as well as putting mobile phones away and staying hydrated. A key thing drivers should do is “put their pride in the back seat” and stop viewing other drivers as challengers. “Don’t challenge the other road user by speeding up or attempting to hold your own with them.”

But if it is a real problem – if you find yourself getting that tunnel vision, or getting so angry you’ve contemplated getting out of the car for a row – then you need to remove yourself from that situation. Stop driving, and seek help in learning to relax and avoid flying off the handle. Getting to the root of your anger is the only way you can learn to control it.