Grainne’s Gap, Dolphin’s Barn, Bundle of Sticks, Hackballscross… One of the best things about Ireland is the weird and wonderful place names across the country. If you’ve ever heard these names and thought “is that a real place?” – or wondered who Grainne is, why Borris is in Ossory and what happened to the old Twopothouse – here are your answers.

What did you just say?!

Photo by sarah777

Some place names catch the ear for the wrong reasons. You might worry about works on the “effin road”… but Effin is a parish in Limerick, where Saint Eimhin had a church.

Termonfeckin in Louth, similarly, honours Saint Feichin (Tearmann Feichín: Feichin’s refuge). An old church weathervane gave Brasscock in Waterford its name, while Nobber in Meath anglicizes An Obair (The Work), possibly referring to the construction of a Norman motte-and-bailey.

The first syllable of Foulksmills in Wexford is open to debate: does it rhyme with “poke” or “puck”? It’s named after a fifteenth century Sir Fulk Furlong, who was… Lord of Horetown. Spelling varies wildly in the records – Fulk, Fook, Fuch, Foulk – which explains the divergent pronunciations. (We’ll stick to “Foke”.)

Horetown and the seaside townland of Bastardstown, 20km to the south, are both probably names after unfortunately named Anglo-Norman families who once lived in the area.

And the Dry Arch Roundabout in Letterkenny seemingly took its name from a viaduct demolished in the 1990s: a dry arch, rather than an aqueduct. A bridge in Antrim has the same name.

Mind the gaps

Photo by TenthEagle

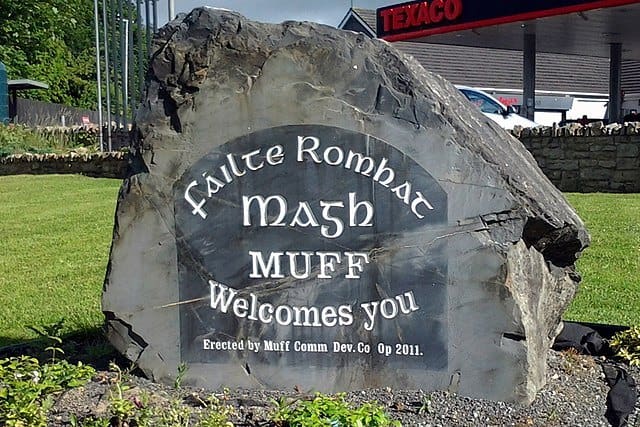

Grainne’s Gap near Muff in Donegal – local lore links it to the legend of Diarmuid and Grainne, who ran across Ireland avoiding Fionn MacCumhaill – several places in Donegal and Sligo are known as “Diarmuid and Grainne’s Bed”, where they reputedly camped during their odyssey. While we’re here, Muff comes from Magh, meaning plain; the same word gives us Mayo (Maigh Eo: yew plain).

Moll’s Gap in Kerry is named after Moll Kissane, who ran a shebeen there fadó. And the most likely origin for Wicklow’s Sally Gap isn’t Sally, but Saile, Irish for willow.

Leopards and dolphins and goats, oh my…

Photo by William Murphy

Looking at a map of Dublin, you’d be forgiven for thinking the city was a menagerie. Sadly, most of the zoological names are misnomers: Dolphin’s Barn never housed aquatic mammals, but was home to the Dolfyn family from the 1200s on. The Phoenix Park rose from water rather than ashes: the Irish Fionn Uisce (clear water).

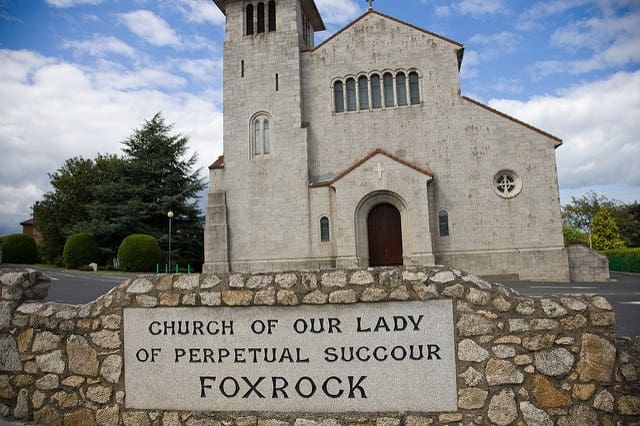

Everyone’s favourite interchange, the Red Cow, is named for a pub (see below). The jury’s out on Foxrock – it either comes from foxes or from Thomas Foulkes, a landowner in nearby Shanganagh. And while Leopardstown evokes images of big cats, its origins are less salubrious – not leopards, but lepers, kept outside the city. (It shares a dubious honour with Tallaght, which, charmingly, means plague pit.)

There are some places named for animals – goats did frolic in Goatstown. Less obviously, Glenamuck and Glenageary mean Valley of Pigs and Valley of Sheep respectively in Irish, and, in Kildare, Leixlip is Norse for Salmon Leap.

Inns and Pothouses

Photo by Seighean

It’s said that we Irish only give directions via pubs, which may be why so many places are named after them. The two crossroads of Newtwopothouse and Oldtwopothouse in Cork took their names from a nearby inn, which had two ale-pots at the door and was a coach stop on the 1700s Cork-Limerick route. Oldtwopothouse eventually became better known as Hazelwood, after the lords of Hazelwood built a hall there.

Other places named after inns include the obvious ones – Twomilehouse (Kildare), Twomileinn (Limerick and Cork) and Threemilehouse (Monaghan) – along with Blue Ball in Offaly, The Pigeons in Westmeath and Horse and Jockey in Tipperary. Dublin’s Red Cow seemingly took its moniker from an eighteenth-century tavern called The Shoulder of Mutton, whose sign had a red cow. Nowadays, pub, area and interchange share one name.

Is that a real place?

Photo by sarah777

Given that it’s just off the M7, the Bundle of Sticks Roundabout is subject to the same reaction from a lot of people: “Is that a real place?!”.

Yes, it is. The name is older than the roundabout – when it was briefly labelled it the “Newhall Roundabout” back in 2004, a consultation found that locals would rather stick with the name the area had always been known by: the “Bundle of Sticks”.

While it sounds odd in English, the Irish equivalent Brosna is quite common: Brosna (Kerry), Bunbrosna (Westmeath), Brusna (Roscommon), the River Brosna, etc. Less specifically, the word can mean twigs or firewood – fittingly, as the roundabout went on fire once, in 2014.

Another placename that seems like it shouldn’t be real is Hackballscross in Louth. The origin is unclear – one record from the Placenames Database links it to an 1840s story featuring a horse nicknamed Hackball. Other sources suggest gory tales of burglars and axes, probably urban legends. Maybe we’re better off not knowing…

Who’s Borris and what’s he doing in Ossory?

Photo by sarah777

Borris appears in several placenames, either on its own (the town in Carlow), or part of longer names around Laois and Tipperary. Nothing to do with Yeltsin, Johnson or Becker – it comes from Buiríos, meaning burgage, an old word linked to borough.

Twomileborris is simply a two-mile borough, Borrisoleigh is O’Lea’s Burgage and Borrisokane is Burgage of the Cianacht. Borris-in-Ossory may conjure images of ossuaries and bones, but it harks back to the ancient Kingdom of Osraige, which occupied much of modern-day Laois and Kilkenny.

Pushing forward

If you’ve ever wondered what French would sound like with a Cork accent, Buttevant is your answer. The village’s name has an unusual origin: the French phrase Boutez-en-avant, meaning push forward. This was apparently the motto and/or battle cry of David de Barry, who started Buttevant’s markets and fair in the 13th century.

Common names from Irish

Photo by sarah777

It sometimes seems like every second place starts with Bally- or Ballin-. That usually derives from baile (place or town), so Ballybane is the white place (an bhaile bán), Ballyjamesduff is the town of Black James (Seamus Dubh), etc.

The Irish for village, incidentally, is Sraidbhaile (one-street-town)… so the villages of Stradbally in Laois, Waterford and Kerry are just called Village.

Ball- can also come from béal (mouth), as in Ballina (Béal an Átha: mouth of the ford), Ballinasloe (Béal Átha na Slua: ford-mouth of the crowds) and Ballylongford (Béal Átha Longfoirt: ford-mouth of the anchorage).

Áth (ford) is surprisingly common, found in places like Athlone (Luan’s Ford), Athy (Ae’s Ford) and Athenry (King’s Ford). Maybe in parallel universes Dublin is called Athclea or Ballinaclea (from its Irish name Baile Átha Cliath) or even Blackpool: the city’s English name derives from Dubh Linn, a dark pool in the Liffey in Viking times.

Photo by Jennifer Boyer

You can be reasonably sure that anywhere with Rath or Lis had a ringfort: Rathfarnham is Fearnan’s ringfort, Rathkeale is Caola’s ringfort and Lismore is the big ringfort. Dún (Dundalk, Dunshaughlin, Donegal, etc) is another word for fort, though not necessarily a circular one. Rathdown (Rath an Dúin) and Lisdoonvarna fall into the so-good-they-named-it-twice category (Ringfort Fort and Ringfort Fort of the Gap).

Kill sounds funny to foreign ears but just means churchyard or graveyard, so “Kill in Kildare” is “the churchyard in the oak churchyard”, Kilkenny is Cainnech’s Church(yard), Kilmacthomas is McThomas’s churchyard, etc.

Drum (Drumlish, Drumshanbo, Dromahair etc) means ridge (Dromahair, intriguingly, means Ridge of the Two Demons), and Tubber, comes from tobar meaning well. While a well of curry might sound like a great idea after a night out, sadly, Tubbercurry just means the well of the corrie (a type of valley).

Finally, a special mention to…

Muckanaghederdauhaulia and Glassillaunvealnacurra. The two Galway townlands share the record for Ireland’s longest townland name. They mean “pig-shaped hill between two saltwater lakes” and “green isle at the weir-mouth”. So now you know.